Biden’s climate bill was too tame, here are four fixes

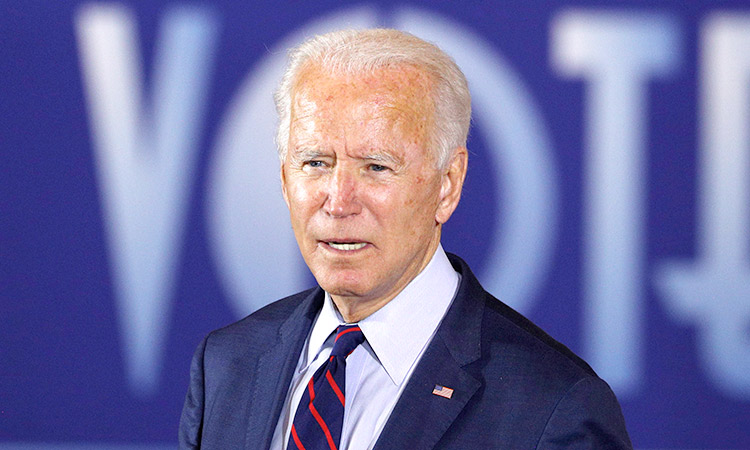

President Joe Biden signs the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 into law during a ceremony in the State Dining Room of the White House in Washington, DC. Tribune News Service

Mark Gongloff, Tribune News Service

In a perfect world, America’s major political parties would argue not about whether to fight the climate change fuelling devastating heat waves across the country, but how to fight it. In our imperfect world, one party has vowed to do more on climate. The other party has vowed to do … the opposite of that. A year ago this week, President Joe Biden and fellow Democrats in Congress passed the Inflation Reduction Act, the biggest US climate bill in history. But it was far from perfect. It left the US with no realistic path toward meeting its stated goal of zeroing carbon emissions by 2050. At the rate we’re still pumping planet-heating carbon into the atmosphere, today’s heat waves could come to seem downright pleasant.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer vowed recently to enact more climate legislation should Democrats gain filibuster-proof control of lawmaking in the 2024 election. Republicans, meanwhile, have detailed plans to dismantle the IRA and Biden’s other climate actions if they retake the White House and Senate. Building things is hard. Wrecking them is easy. The GOP needs no help in demolishing climate progress. So, assuming a 2025 in which America is run by politicians who are serious about the climate, here are some helpful ideas for an IRA II that may not be perfection, but at least strive in that direction.

Make Carbon Expensive: The IRA’s tax breaks for clean energy will help curb emissions, but they aren’t nearly enough to meet net-zero goals. A follow-up IRA should push companies to cut emissions faster, either by making them pay a price in a carbon market, or by establishing a federal clean-energy standard that penalises energy producers for transitioning too slowly from fossil fuels. The Biden administration has floated both ideas, only to have them shot down by political opposition (including from Democrats). That leaves the US and Australia as the world’s only two developed countries that don’t charge a price for spewing carbon into the atmosphere. And Australia this year took a step in the right direction, forcing industries responsible for about a quarter of the country’s carbon pollution to cut emissions or buy credits. As history’s biggest emitter, the U.S. has no good excuse for trailing its peers so badly on carbon pricing.

“One of the real limitations with the IRA was that it contained carrots for renewables, but no real stick for fossil fuels,” climate scientist Michael Mann of the University of Pennsylvania said in an email. “I would like to see provisions that not only incentivize clean energy but dis-incentivize fossil fuel energy.” That should also include killing a self-defeating IRA rule that the government cannot issue new offshore-wind leases without also issuing new offshore oil and gas leases. The important thing is to make sure there are enough financial incentives and goals in place that the whole economy is cutting carbon as quickly as possible. “When the goal is zero emissions, you can’t have any backwaters enabling laggards to lag,” said Kristina Dahl, principal climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “So we need to set some actual standards and act like we want to actually see change.”

Permissions, Please: Clean energy is cheap and getting cheaper. It costs less to install and run new solar and wind power equipment than it does to start up new fossil-fuel plants. Investment in clean power has surged to nearly equal that of its dirtier counterpart. That’s the good news. The bad news is that getting government permission to build clean-energy facilities and connect them to the power grid is needlessly difficult.

Red tape and Nimbyism are the enemies of progress here. As Bloomberg’s editorial board has written, endless environmental reviews and lawsuits are strangling clean energy projects. More than 1250 gigawatts of clean power and 680 gigawatts of storage projects are stuck waiting for the go-ahead to connect to power lines, according to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Wait times have ballooned to nearly four years. A second IRA would include the permitting reform necessary to get these projects built and providing juice much more quickly. Such measures were dropped from the first IRA, and a revival is overdue. In a move that could appease the Nimby crowd, a new climate bill could also push to build clean-energy projects on unloved lands such as brownfields or abandoned mining sites, suggests Laura Brannen, senior policy adviser and federal climate policy lead at The Nature Conservancy. Anything to get as much clean power built as quickly as possible.

“If we want to meet timelines to reduce emissions, we have to build wind and solar at a totally unprecedented rate,” said Ethan Coffel, a climate scientist at Syracuse University. While we’re building new energy and transmission lines, we’ll also need funding to ramp up charging infrastructure for electric vehicles, including long-haul trucks. Might as well dedicate some funds to bolstering public transportation while we’re at it.

Adaptation and Resilience: While we should do everything we can to slow warming and avoid even worse consequences, it’s also long past time to climate-proof our homes, offices and infrastructure against both current and future catastrophes.

A meaningful IRA II would provide funding and government stewardship for adaptation and resilience, especially in vulnerable communities most at risk from global heating. It would also establish and enforce sustainable and resilient building standards across the country. A strong bill would also address land use, including climate-smart farming policies and incentives to plant more trees. Climate-related disasters inflicted $177 billion in damages last year, numbers that are becoming routine. Spending $1 on adaptation could avoid $6 in future costs, suggested Dahl of the UCS. That’s why spending on resilience isn’t really a cost at all. It’s an investment.

Let’s Be Fair: Just as marginalised communities are on the front lines of climate change at home, developing countries bear the brunt of it around the world. The nations most exposed to heat stress, sea-level rise and other disasters also tend to lack infrastructure, air-conditioning, clean water and more. They’re also the least to blame for the climate emergency. The nation arguably most to blame is the US. Not only does it have a moral obligation to help these countries avoid and recover from climate disaster, it also has something to gain from helping them transition to cleaner energy. Developing nations that burn fossil fuels to raise living standards will only make the climate problem worse. The US should play a central role in securing them green financing.

At home, the Biden administration also must make good on its pledge to direct 40% of climate-related investments to disadvantaged communities. These include not just clean energy but reliable water supplies and transit, sustainable housing, job training, pollution cleanup and more. This all sounds like a big ask, and it is — maybe too big, given the current political climate. But with every year that passes without such action, the costs of addressing our delay will only grow bigger.