Lebanon’s COVID-19 fight is laudable

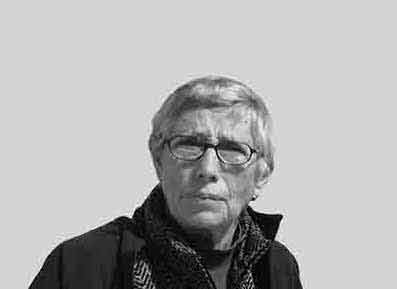

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A nurse at the Lebanese hospital Notre Dame des Secours shows a heart sign with her hands as others dance to music played by a band thanking them for their efforts to support patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, in the northern coastal city of Byblos. Agence France-Presse

Lebanon’s success was unexpected for several reasons. Lebanese are an independent-minded, unbiddable people who resist being told how to behave by their corrupt, inept political elite. Maronite President Michel Aoun and Shia Parliamentary Speaker Nabih Berri, both veteran politicians, have no credibility with the majority of Lebanese. Protesters took to the streets last October have called for their ouster. Drafted from the academic world, new-comer Prime Minister Hassan Diab has little backing from his divided Sunni community and little political clout.

Lebanon’s sectarian system of governance, imposed by colonial France before liberation in 1943, pits one religious community against each other, making it difficult for Lebanese to confront challenges as a nation, a country and a people. Lebanese society is also sharply divided between haves-and have-nots with an uneasy middle class in between. Political and communal rifts surviving from the 15 year civil war (1975-90) have not healed and the country’s infrastructure has not been reconstructed. The lack of electricity, water, rubbish disposal, and sanitation remain major issues. Mismanagement and graft at all levels are rampant.

Nevertheless, the faltering, bankrupt Lebanese administration has managed the virus battle reasonably efficiently. On February 21st, the day the first coronavirus case was confirmed, an information website was established to report on theCovid-19 situation in Lebanon and to publish official and emergency telephone numbers and advice. The 500-bed Rafiq Hariri public hospital on the southern edge of Beirut has been designated as the facility to treat patients who soon followed the first case. The Shia Hizbollah movement has established its own testing and treatment centres around the country, assuming some of the weight of infections. Other political factions have carried out sanitising and offered medical masks and testing to their constituents.

Schools and universities closed a week after the first case appeared. In mid-March Beirut’s international airport suspended traffic except for repatriation flights and the country’s land crossings closed. Churches, shops, businesses, restaurants, cafes, malls, and, from time to time, banks shut. People have been allowed to leave home for urgent errands once a day. The circulation of cars has been restricted according to odd and even license plates. Night time curfew has been imposed.

There is protective equipment for health workers and tests are available for free at government hospitals and for a fee at private clinics. Results are delivered the day after tests and contact tracing is carried out. Face masks, gloves and hand sanitisers are sold in stores and pharmacies and used. Health Minister Hamad Hasan has said medical masks must be worn by people who leave home as the lockdown is eased.

Last Friday, the government announced a five-phase, week-by-week lifting of restrictions beginning on April 27th. Private firms may reopen on May 11th if distancing is observed while the public sector will continue to operate with minimum staff. The opening of schools, universities, and public places will not proceed until the last phase. Conference, concert and festival halls will remain closed.

There is serious concern, however, that the virus could spread among Lebanese if there are large outbreaks in poor Palestinian refugee neighbourhoods or informal Syrian refugee camps. Syrians who might like to go home cannot as the borders are closed.

Meanwhile, the politicians squabbled over essential reforms while the economy collapsed. Protesters have left lockdown to return to the streets to condemn the precipitous fall of the gradually declining Lebanese Lira from 1,507 to 4,000 to the US dollar. Food and fuel costs are soaring, many cannot pay rent.

Restaurants, cafes, shops, and businesses have closed. Tourism, a main money-earner for the economy, is non-existent. Le Bristol, a landmark hotel in West Beirut, has closed its doors. More than 220,000 jobs were lost in the private sector betweem October and February. Financial transfers from family members living abroad have dried up. For the first time ever, Lebanon defaulted on foreign loan payments last month.

Fresh demonstrations have been staged in Beirut, Tripoli, the protest hub, and the Bekaa where the poverty level stands at nearly 60 per cent. Those taking part are grim, unlike the early days of the protest when cheerful, optimistic Lebanese celebrated freedom and what they hoped would be an end to the regime. In Tripoli people are defying the lockdown to go to reopened markets.

Last week, irresponsible lawmakers left an emergency session of parliament before it could vote on the relief package for the poor and other key measures. The Lebanese people have waged their battle with the coronavirus but the politicians have not even tried to tackle the political and economic collapse of the country.

Why have the Lebanese succeeded in the fight against the coronavirus when so many well-run, well-resourced countries have not? Lebanese have a broken government with no authority not an authoritarian regime which can impose strict measures on the population. The state’s resources are depleted to the point of bankruptcy. Consequently, fear is a key factor. Lebanese believe that if they get ill, they will not receive live-saving care in underfunded public health care facilities or even at private hospitals. They fear that medicine, which has to be imported, will not be available. For Lebanese who have suffered repeated loss of control over their lives due to civil war and Israeli attack, lockdown represents control and protection. Bombs and shells are solid objects which explode, wreaking death and destruction; the coronavirus is invisible, unknown, unpredictable and steals into the homes, work places, and lives of its victims.