The huge, rightful uprising must succeed

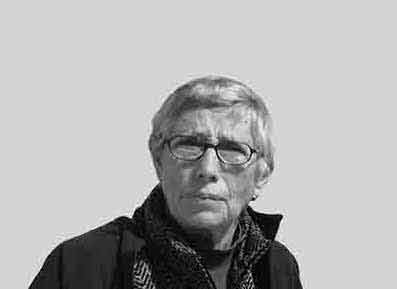

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A university student releases candle balloons during a student festival in Najaf, Iraq, on Saturday. Reuters

He has the backing of protesters, the nationalist cleric Muqtada Al Sadr and his bloc, the largest in parliament, and opposition parties, but has been sharply criticised by the powerful pro-Iranian factions.

Salih’s resignation would deepen Iraq’s three-month political deadlock.

According to the constitution, deputies would have to choose his replacement who would nominate a prime minister. This would involve political wrangling and waste time during a crisis Iraq cannot afford to delay. Iraq is currently governed by a caretaker cabinet headed by Adel Abdel Mahdi, a compromise figure originally chosen by rival parliamentary factions because he has neither party nor militia backing. Consequently, he was always a weak figure.

So far, two names have been proposed. Outgoing Education Minister Qusay Al Suhail turned down the nomination while activists dismissed Basra Governor Asaad Al Edani, backed by a pro-Iranian bloc, because he had ordered security forces to use lethal fire on protesters. Iraqis have taken to the streets since October 1st to protest the lack of electricity, potable water, jobs, and security caused by sectarianism, mismanagement and corruption.

Nearly 500 people have been killed and 17,000 injured while protesting. The object of the uprising is not only a change of prime minister and cabinet, but the transformation of Iraq’s governance from an ethno-sectarian parliamentary system into a secular presidential system. The sectarians in power oppose this total change of regime.

While Iraq’s parliament has adopted a new electoral law, a key demand of the protesters, this legislation is unlikely to satisfy them. Under the law voters would elect legislators as individuals from representing their electoral districts rather than from party lists. However, unless the ethno-sectarian model, imposed by the US occupation regime in 2003, is scrapped and the ruling political parties are dissolved these parties will simply put forward candidates in constituencies in order to maintain their grip on power.

Meanwhile, Iraqi military men falsely blame the uprising for the revival of Daesh which has re-emerged after losing its territorial “caliphate” which stretched from Raqqa in north-central Syria to Hawija in north-eastern Iraq. Laying the blame on the protesters amounts to an attempt to explain away the failure of the Iraqi army and associated militias to rid this region of the Daesh menace and of the government to pursue seriously reconciliation with persecuted and resentful Sunnis.

Kirkuk province’s Hawija district has become a centre for the revival of Daesh and a base from which to launch attacks on Iraqi forces and anti-Daesh civilians. Daesh survivors have no option but to go underground, rearm, and fight.

They are outcasts no governments want on their soil and have become forever fugitives. Furthermore, they are said to have large financial resources on which to depend as well as Sunni alienation and hatred of the current system and government.

Hawija was the last Iraqi town captured from Daesh by government forces in 2017 during the campaign to destroy the territorial base of Daesh. Hawija is both strategic and economically important. Hawija is strategic because it is located between two main highways: the route from Baghdad to the oil-rich city of Kirkuk and the route from the capital to Mosul, once Iraq’s second largest and most populous city. Hawija is also located in a green agricultural region which provides vegetables for markets across the country.

Daesh is rooted in the Hawija district because the population consists of mainly Sunni Arab urban dwellers and tribesmen who abjure both the pro-Iranian, Shia fundamentalist dominated regime in Baghdad and neighbouring Kurds. Like Falluja in the western province of Anbar, Hawija strongly resisted the US occupation of Iraq. In 2013, hundreds of civilians were killed in anti-government protests in the Hawija district.

The brutal crackdown by Baghdad deepened anti-Shia sentiments, particularly against former Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, who persecuted, jailed and slew Sunnis opposed to the regime installed by the US. Therefore, there is a blood feud between Baghdad and Hawija as well as other Sunni cities and areas.

This blood feud could, ultimately, be resolved if and when Iraq’s protesters depose the sectarian regime. A return to secularism could restore the country’s sectarian balance and communal coexistence that had prevailed in Iraq before the US invasion and occupation which used this divide-and-rule model to prevail in Iraq. This did not succeed and the US was compelled to withdraw its troops and political cadres at the end of 2011, leaving the country in chaos. The uprising seeks to restore national unity and popular sovereignty and to use the country’s annual oil revenues of $60-70 billion to rebuild and benefit the population rather than to swell the foreign bank accounts of corrupt politicians and officials. The uprising must succeed if Iraq is to recover from nearly 17 years of division, misrule and graft.