Sundaram Tagore New York to host artist Anila Quayyum Agha’s works

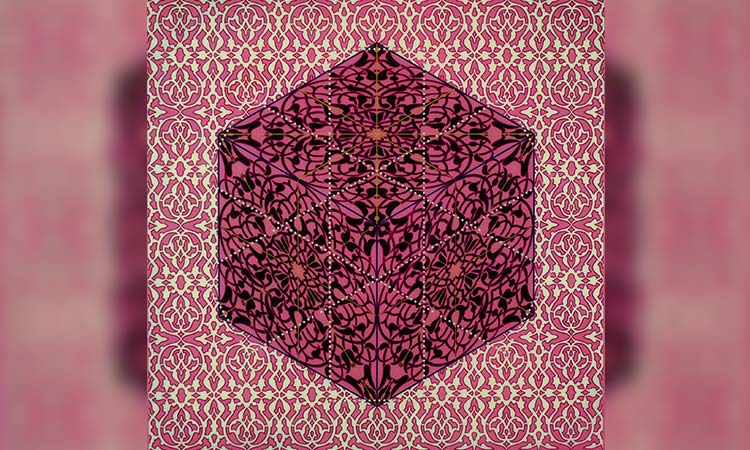

A Beautiful Despair — artwork by Anila Quayyum Agha.

Muhammad Yusuf, Features Writer

Sundaram Tagore Gallery is set to host an exhibition titled Anila Quayyum Agha: A Moment to Consider (Sept. 8 – Oct. 8) in its New York spaces. It consists of new paintings, drawings and light installations by acclaimed Pakistani-American artist Anila Quayyum Agha, known for her immersive, illuminated, suspended cubes.

This is Agha’s first solo exhibition at Sundaram Tagore New York. Agha’s work has been the subject of eight museum shows since 2019. For this exhibition, she reimagines ornamental patterns from history in metal, resin and paper using traditional and contemporary techniques of craft.

The work, which ranges from monumental laser-cut steel sculptures to intimate hand-embroidered drawings, pays homage to artists and craftspeople who historically have gone unrecognised and unnamed, despite the importance of their artistic output.

The show’s centerpiece is an immersive large-scale light installation commissioned by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Texas in 2021.

A Beautiful Despair is part of Agha’s award-winning cube series, which garnered critical recognition and drawn crowds in museums and public spaces around the world since 2014.The laser-cut patterns that embellish the lacquered-steel sculpture are the artist’s reinterpretation of floral and geometric motifs found in Islamic art and architecture in Asia and Africa.

Agha also debuts Stealing Beauty (Steel Garden – After Durer’s A Great Piece of Turf), an expansive three-dimensional light installation created especially for the exhibition.

READ MORE

Butter becomes 8th BTS video to cross 800 mn YouTube views

Rousing poetry is greeted with ringing applause at Jashn-E-Hind

Rakul Preet opens up about working with Akshay Kumar in Cuttputlli

The mirrored stainless-steel layered wall-relief is laser-cut with sinuous floral patterns comprising visual elements from South Asian Islamic culture enmeshed with motifs by the 19th-century British textile designer William Morris, who was inspired by Islamic art and architecture he encountered in his travels.

When activated by multiple light sources, the gleaming installation casts a jungle of flora-shaped shadows that seem to flutter on the wall; it is a metaphor for the tangled complexities of contemporary life.

The exhibition also marks the debut of a series of resin paintings in which the artist expands her use of colour and explores pattern in new ways. Agha departs from her characteristic streamlined palettes in favour of vivid hues inspired by the high-contrast colour combinations popular in South Asian and African textiles.

The vivid colours accentuate both the pattern and the areas of negative space, which, up till now, had been set against a simple white or black background in her embroidered works or hollow in her sculptures.

Agha’s labour-intensive process involves building up the surface in stages, with layers of coloured resin applied over a substrate.

The process can take from twelve to sixteen hours per design. Colour is delicately poured by hand to fill the precisely incised grooves. After approximately 24 hours, when the resin has hardened, the surface is levelled, and the process begins again with the next colour. Each work is composed of six to twelve colours.

Although produced with the aid of technology and wholly contemporary in their aesthetic, each work is imbued with history. In addition to the formal elements inspired by traditional Islamic art, the unique application of colours references the centuries-old craft of pietra dura, the decorative inlay technique that flourished in Italy in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Pietra dura was used throughout Europe and eventually in India, notably in the court of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, who commissioned one of the world’s most exquisite examples of the craft, the Taj Mahal.

For Agha, the opulent structure is a source of inspiration and fascination — not just for the sheer beauty of the sumptuously detailed stonework, but the inherent contradiction of one man’s monument to love extinguishing the lives of the thousands of unacknowledged craftsmen who built it.

Also on view will be select works from a series of embroidered drawings recently on view in Mysterious Inner Worlds, the artist’s 2022 solo show at the University of New Mexico Art Museum, alongside new works created for this exhibition.

Agha, who is formally trained in textile design, creates luminous drawings on paper using hand-stitching and beadwork to highlight the disparities in how we evaluate labour based on gender, ethnicity or economic station — a theme she explores frequently in her practice.

Articulated in reflective metallic thread and glass beads, the drawings play with light and shadow in a manner similar to her sculptures. The works on paper are inspired by memories of her mother’s quilting circles, but also reference women’s labour, which often goes without payment or recognition.

“In my artwork, I use a combination of textile processes and sculptural methodologies to question the gendering of women’s works as inherently domesticated and excluded from being considered an art form,” Agha says.

She arrived in the US from Pakistan in 2000, and even while still a student, she was frequently told that as a woman, particularly a woman of colour and an immigrant, she would never advance her career if she continued to use techniques associated with craft or visual elements unique to Islamic culture.

But after seeing exhibitions showcasing the subversive embroidered paintings of Egyptian artist Ghada Amer, the hand-sewn story quilts by African American artist Faith Ringgold and multimedia installations created using textile techniques by American artists Anne Wilson and Ann Hamilton, Agha knew there was space for the kind of art she wanted to make, which was authentic to her life experiences while also conveying universal truths.

She lives and works in Augusta, Georgia, and Indianapolis, Indiana.