The reluctant hero

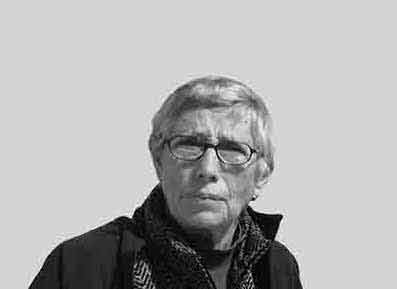

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A protester carries a portrait of Judge Tarek Bitar in Beirut.

Bitar charged Hassan Diab, who was prime minister at the time of the blast; Ghazi Zeiter, then minister of transport and public works; and Ali Hassan Khalil, a former finance minister, with homicide with probable intent. He accused Public Prosecutor Ghassan Oueidat, two security chiefs, and other officials with obstructing the probe.

Ouedidat responded by accusing Bitar of exceeding his authority, “rebelling against the judiciary” by reopening his probe without permission, and ordered the rejection of his warrants, summons, and documents. Oueidat also released 17 port officials and employees detained three days after the explosion and banned Bitar from travelling abroad.

Oueidat’s actions are intended to prevent Bitar from proceeding with his investigation but he has declared he will continue with his mission, risking his life. As he has been threatened, he and his family have police protection. His predecessor military judge Fadi Sawwan was also threatened and was compelled by the judiciary to stand down when he insisted on investigating figures Bitar has charged with homicide.

Bitar has challenged the authority of Queidat and the Higher Judicial Council to dismiss him. After a review of his legal status conducted before renewing his mission, he found that, according to a 2001 code he can only be dismissed by the government. It is ironic that he was appointed in February 2021 by Diab who is blamed by Bitar for failing to act on repeated warnings about the dangers posed by the ammonium nitrate.

An academic recruited to head a technocratic cabinet, Diab does not pose a problem for Lebanon’s political elite. Zeiter and Khalil are untouchables. They are deputies from parliamentary speaker Nabih Berri’s Amal Movement, the close ally of Hizbollah which has opposed the probe whether headed by Sawwan or Bitar, both independent investigative judges.

While Oueidat argues he controls and is the ultimate decider on the port investigation, Bitar has called upon him to recuse himself because he was in charge of a 2020 security inquiry into the storage of the ammonium nitrate in the port. As a result of this intervention Syrian workers were dispatched to repair the warehouse. It is suspected that sparks caused by welding an iron door may have set off the deadly and destructive blast, regarded as the largest non-nuclear explosion since World War II.

Bitar, 49, was born into a Greek Catholic family in the village of Aydamun in the Akkar region of north Lebanon. He earned his law degree from the Lebanese University in 1999 and went into private practice until 2010 when he became the sole criminal judge in the port city of Tripoli. In 2017, he was chosen to head Beirut’s criminal court. In both posts, he conducted investigations into sensitive cases and was threatened when he dealt with a drugs case. He has a reputation for being incorruptible, hard working, and exacting.

As he says he has no partisan affiliation and has scrupulously avoided connections with politicians and business interests, he was seen as a neutral judge by the range of factions. However, Bitar began by following the example of judge Sawwan by charging key members of the ruling establish-ment. Bitar has been accused by Amal and Hizbollah of bias and taking orders from the US embassy in Beirut, derided by television commentators and blackguarded by partisans of figures he has charged.

Nevertheless, he retains the support of the families of victims of the Beirut blast, independent deputies, opposition parties, pro-reform legal organisations, and a large percentage of the public. Last Sunday, the influential Maronite Christian Patriarch Bechara al-Rahi called on Bitar to “continue his work to unveil the truth and issue indictments.” The prelate urged Bitar to “seek the assistance of any international authority” to complete his mission.

In October 2021, his investigation sparked clashes when snipers from the right-wing Christian Lebanese Forces fired on pro-Hizbollah and Amal supporters who were protesting against Bitar outside the Justice Ministry which is located near the frontline between warring East and West Beirut during the 1975-1990 civil war. Seven people were killed and 30 injured in the exchanges.

The probe was suspended in December 2021 after three cabinet ministers filed charges against Bitar. However, the Court of Cassation could not remove him as a quorum was impossible due to the retirement of several judges.

Bitar’s unexpected return has coincided with Lebanon’s worst ever crisis. Factional infighting has left the country without a fully functioning government, a president and a responsible parliament. President Michel Aoun refused from May until he stepped down in October to approve cabinetline-ups proposed by designated Prime Minister Najib Mikati. This has left Lebanon with a caretaker government which cannot take decisions needed to enact reforms which are required for Lebanon to receive $21 billion in international financial aid. Parliament has tried and failed a dozen times to elect a new president.

Aoun knows what this stalemate means: desperation leading to the election to the presidency of his son-in-law, Gibran Bassil, who is said to be the most unpopular man in Lebanon. A former army commander allied to Hizbullah, it took 29 months and 45 sessions of parliament to elect Aoun despite his violent opposition to the Taif Accord which was to end the country’s civil war but extended hostilities for 18 months.

The economy is in free fall, there is no foreign currency to pay for fuel, food, and medical imports, the Lebanese Lira has plunged from 1.500 to 58-63,000 to the dollar, and 80 per cent of the population lives below the poverty line. At this low point, Tarek Bitar’s defiance of the politicians behind the country’s collapse is seen as a ray of light in the long, dark corridor of Lebanon’s tragic and terrible dissolution.

Photo: AFP