Did Biden’s Democracy Summit fail to create magic?

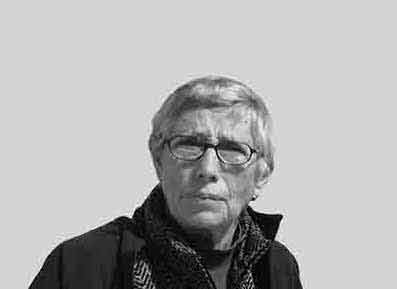

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

President Joe Biden delivers the closing remarks to the virtual Summit for Democracy, in the South Court Auditorium on the White House campus, on Dec.10, in Washington. Associated Press

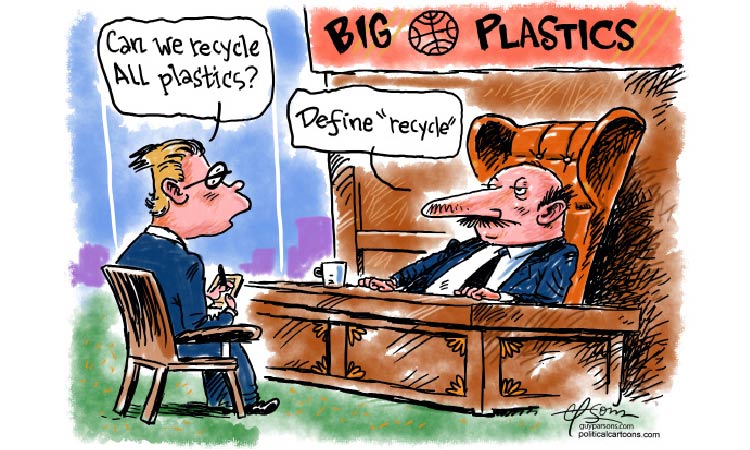

US President Joe Biden’s Summit for Democracy was a public relations ploy rather than a means to commit participants to improve their democratic credentials. He convened this virtual talk fest at a time three of the world’s largest democracies — India, the US, and Brazil — have been backsliding and are categorised by the Democracy Index as “flawed democracies.” He also hosted the two-day event during a year when there have been six military coups, including in Myanmar and Sudan. In fact, the majority of the 110 countries invited to Biden’s summit are, like the US, “flawed democracies.” The list was drawn up by a US citizen of Indian origin, Shanthi Kalathil, who is Biden’s coordinator for democracy and human rights in the National Security Council. She and her colleagues clearly chose to invite some on the basis of their close relations with or usefulness to the US. The Philippines, Poland, and Israel are prime examples. But the Philippines and Poland are seriously “flawed” due to their authoritarian leaders and Israel because of its marginalisation of and discrimination against its Palestinian citizens, who account for 20 per cent of the population.

Of course, Israel would not be excluded because of its illegal colonization of Palestinian land, which the US opposes, and oppression of Palestinians living in East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza. Despite its record of human rights abuses, Pakistan had to be invited because backsliding India was on the list. Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan was the sole leader who said “no” to the invitation. It is significant that more half of those invited did not attend without rejecting the invitation. Among the African leaders invited, eight took part while 10 did not, notably political and economic powerhouse South Africa. The rate of absentees from the Americas amounted to a boycott: only three countries took part — the US, Belise and Costa Rica while 24 did not, including US neighbours Mexico and Canada. Of the 20 countries from the Asia-Pacific region only six participated, including India and the Philippines. By contrast, 36 countries from Europe attended while three did not: Armenia, Georgia, and Ukraine. Of the two initiated in West Asia, only Israel joined, Iraq did not. Consequently, the virtual event became essentially a white men’s discussion group. Non-governmental organisations and human rights groups complained about being sidelined. Furthermore, Biden’s summit did not attract the wide attention in the media he anticipated

and was sharply criticised by both thoughtful and scornful people in the US and dismissed by antagonist China, Nato ally Turkey and European Union member Hungary which were not invited. Writing in the Washington Post on December 6th, Ashley Parker and John Hudson argued that the list of invitees seemed to “divide the world into good guys and bad guys.” Those left out see “Biden, like a global Santa Claus, declaring that specific countries are naughty or nice, and will be treated accordingly.” It is ironic that the themes of the summit were, the authors said, “defending against

authoritarianism, addressing corruption, and promoting respect for human rights” at a time the US itself if beset by the authoritarianism of Donald Trump, the growing corruption of its political system, and white disrespect for fellow citizens of colour.

Writing in Foreign Affairs in 2020 in an article entitled, “Why American Must Lead Again: Rescuing US Foreign Policy After Trump,” Biden pledged, if elected, “To take immediate steps to renew US democracy and alliances, protect the United States’ economic future, and once more lead the world.” He has done very little to honour these pledges and has not restored US leadership in a world afflicted by deepening divisions, warfare, economic decline, and political drift. While covid has to assume some blame for deflecting Biden from meeting his campaign commitments, he simply does not have the personal drive and determination to act when action is warranted. On the domestic scene, he has has failed to convince even a few Republicans to join Democrats in adopting and implementing policies beneficial for the majority of US citizens. Republicans are too afraid of Trump to grant bipartisan support. Biden is also challenged by a number of right-wing and left-wing Democrats who are critical of the president and his broad initiatives.

If Biden cannot impose order in his own house, how does he think the US, during his watch, can lead the world? The extent of absenteeism from his virtual summit amounted to a vote of no confidence. Biden’s Democracy Summit was not even his own idea. The first such gathering was held in 2017 by the Alliance of Democracies Foundation, a non-profit organisation estabished by Anders Fogh Rasmussen, ex-Nato secretary general and former prime minister of Denmark. Since then the Foundation has held annual summits which are attended by political and business leaders from

the world’s democracies. The object of these summits is to debate the security and economic challenges faced by democracies and analyse the impact of technology on democratic norms. Biden. as a private citizen, took part in the 2018 Democracy Summit in Copenhagen.

Writing in Politico on December 5th, James Goldgeier and Bruce Jentleson argued, “Biden’s Democracy Summit Was Never a Good Idea” and offered suggestions for an alternative along the lines of the Copenhagen events by involving USAID, institutions, human rights organisations, and businesses. The authors warned last December that inviting leaders of countries “would inevitably create tensions, and that the entire concept of a democracy summit relies on an overly ideological approach to managing the global agenda.” They pointed out that the US had “questionable credibility to position itself as a leading democracy,” especially after the January 6th, 2021, assault on the Capitol building, the home of the US legislature, mounted by Republican Trump supporters to prevent Biden from being confirmed as president-elect in Trump’s continuing campaign to overthrow the 2020 election.