The endless agony of long-suffering Afghans

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

A group of Afghan and foreign nationals sit aboard a military aircraft to be airlifted out of Kabul. AP

Trump did not get his quid pro quo. The Qatar-brokered negotiations in Doha did not progress. Certain it would prevail on the battlefield, the Taliban was not prepared to make concessions to the government and Al Qaeda and other radical groups deployed fighters in the Taliban’s campaign to seize control of Afghanistan.

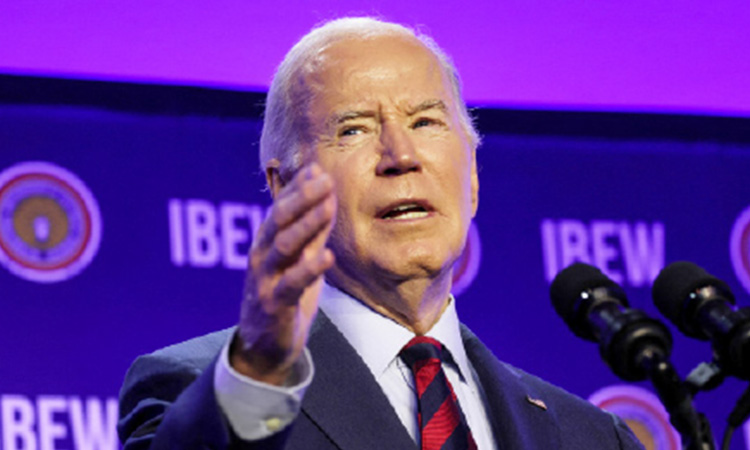

Biden could have used the Taliban’s failure to meet its commitments to backtrack on withdrawal and demand the Taliban negotiate a viable power-sharing deal with the Afghan government and expel radical militants from the country. Instead, he extended the deadline for the US military pullout to August 31st in order to celebrate a public relations feat on September 11th while commemorating the 20th anniversary of the attack on New York and Washington. Biden expected this would boost his standing with US voters and the public in general.

The Taliban responded to Biden by systematically seizing villages, towns and provincial cities before sweeping into the capital unopposed. To add insult to injury, Al-Qaeda-linked Khalil Haqqani — on whose head the US has put a bounty of $5 million — was delegated to go to the presidential palace to order President Ashraf Ghani to surrender, prompting him to flee rather than capitulate. Although labelled a “foreign terrorist organization” by the Obama administration, the Haqqani network — an offshoot of the Taliban which fields Arab, Chechen and Uzbek fighters — was also put in charge of providing security for Kabul.

According to former US ambassador to Kabul Ryan Crocker, Biden began to push for US withdrawal as soon as the Obama administration was in office. Ahead of being inaugurated as vice president, Biden paid a visit to Kabul where he had a row over dinner with Afghan president Hamid Karzai. This event, apparently, solidified Biden’s commitment to withdrawal.

This became a personal crusade. He viewed US military campaigns through the prism of the deployment to Iraq of his elder son, Beau — who died of brain cancer in 2015 — was a key factor in his decision once he became president. He has also repeatedly said he did not want US troops dying in order to protect Afghan women from Taliban strictures and abuses.

While a senator, Biden voted for the Iraq war, but he did not want his son sent to Iraq.

However, Biden adopted a practical approach, stating, “I don’t want my grandson or granddaughters going back in 15 years, so how we leave makes a big difference.”

Unfortunately, Biden was so keen for the remaining US troops to depart that he forgot his earlier words. He, like Trump before him, ignored the manner of their leaving. How foreign forces depart does matter.

Biden relied on “gut” feelings rather than expert advice, careful consideration of the situation and workable options for withdrawal. Chaos has ensued at the international airport in Kabul where thousands of foreigners and frightened Afghans have gathered in the hope of escaping Taliban rule.

Biden’s unilateral decision-making on Afghanistan has alienated NATO allies which had hoped for good relations after four years of Trump’s hostility. But, Biden did not consult them ahead of ordering the US withdrawal from Afghanistan although non-US NATO members had 7,000 troops in the country which they agreed to pull-out when Biden decreed abandonment in April.

Former NATO secretary general Jaap de Hoop Scheffer told the BBC that NATO should not have gone along with the US, arguing that members could have easily have made up the 2,500 departing US forces. He did not, however, address the pullout of 15,000 US contractors who provided maintenance for US-made equipment and vehicles, logistics, intelligence, and communications and air support for the Afghan army. The replacement of the contractors would be far more difficult to achieve.

Armin Laschet, the conservative candidate who could succeed Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel, dubbed the troop withdrawal “the greatest debacle that NATO has experienced since its foundation”.

This debacle has exposed NATO members, including, the US to political and military pressure by Russia and China as well as potential attacks by radical fundamentalists re-energised and emboldened by the alliance’s failure to contain and counter the Taliban, create a stabilising force for Afghanistan, and exert pressure for Afghan government reform.

Critics of NATO’s supine acceptance of Biden’s diktat argue that the alliance has to shift from its long-standing reliance on the US, increase defence budgets and adopt an independent approach to security. The Afghan debacle is likely to compel non-NATO US allies, including those in this region, to reconsider their ties to Washington, which they had hoped would resume its role as a reliable partner after four years of the erratic and unreliable Trump. The debacle will not end with the multi-nation effort to rescue foreigners and Afghans struggling the leave the country in front of the world’s satellite television cameras. The catastrope will continue for the Afghan people who will have to live under and deal with the Taliban emirate which, if it fails to regularise relations with the West and the international community will not be able to feed and clothe the population.

For decades, Afghanistan has depended on foreign funding and humanitarian aid to keep the country afloat. Between $9-10 billion in Afghan central bank deposits have been frozen in the US and the International Monetary Fund has halted a transfer of $440 million in funding. Between 75- 80 per cent of the state budget came from external sources. Last year Afghanistan received $4.9 billion in US aid alone. This has been cancelled by the Biden administration.

The Taliban — which depends largely on the illegal opium trade for funding — will not be able to finance the administration of the state and the cost of sustaining the country’s 38 million people, 47.3 per cent of whom live below the poverty line. Failure to provide could provoke popular unrest, a backlash from opposing militias, civil conflict, repression and more suffering for long-suffering Afghans.