Post Brexit UK becomes Trump’s ally in war on China

Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson welcomes US President Donald Trump at the NATO summit in Watford, Britain. File/Reuters

It is too often forgotten that the Victorian equivalent of Medellin drug cartels imposed unequal treaties on a weakened China, and were backed by the might of the royal navy in doing so.

Contrasting perceptions of that period were painted vividly for me a decade ago when a group of coalition cabinet colleagues were in Beijing waiting with David Cameron to meet the then president, Hu Jintao. We were wearing our Remembrance Day poppies as the annual mark of respect to the fallen in both world wars and subsequent conflicts. A Chinese official approached, his face frozen in horror. The poppy was construed as a deliberate reminder of Chinese humiliation by opium: the meeting would have to be cancelled.

Fortunately we managed to clear up the misunderstanding, but it exposed sensitivities just below the surface about what the Chinese ambassador this week called a “colonial mentality”. And part of that mentality, as the Chinese see it, is the British insistence not just on protecting our liberal values at home (as we should) but imposing them on China.

The peaceful, orderly and dignified British withdrawal from Hong Kong in 1997 was a diplomatic and political triumph for both sides. China could have dealt with the colonial enclaves of Hong Kong and Macau in the same way that India and Indonesia dealt with the remnants of the Portuguese and Dutch empires: military invasion and annexation. Instead the Chinese counted down the clock on a lease originally negotiated under duress.

The handover was conducted under the Basic Law – a national law of China – which has replaced the colonial constitution. Hong Kong is a Special Administrative Region of China in which applies the “one country, two systems” principle, provides legal safeguards for freedom of assembly and speech that do not exist elsewhere in China. There is an inherent tension between the Chinese insistence on territorial integrity and Chinese sovereignty, and the latitude available within the “two systems” for a degree of self-determination. That tension has been managed well enough for 22 years but it is now being tested to destruction.

Why now? There is a range of underlying problems. The high cost and cramped living space of Hong Kong housing are a major frustration, reflecting failures by both the old colonial and the newer pro-Beijing administrations. Meanwhile, many younger Hong Kong residents have never been reconciled to joining the motherland. They have got used to western lifestyles, and are pessimistic about their future after 2047, when a full scale Chinese takeover is permitted by law.

Then Carrie Lam, the chief executive, tried to bring in legislation facilitating extradition to the mainland. She clearly misjudged the public mood and was obliged to withdraw the proposals in response to mass demonstrations. So far, so good.

But the demonstrations continued on a massive scale, and daily. Some protesters were concerned with specific grievances arising from the earlier demonstrations. Some advocated independence. The vast majority were peaceful, but some were not and Molotov cocktails were thrown at the police. In Beijing there was a genuine dilemma. To allow continuing street violence – “chaos” and the breakdown of order on the periphery of China – threatened the “one nation” principle, but intervening to stop the protests would breach the “two systems” principle. Either would be damaging.

An obvious recourse was to deploy the army. In extremis, democratic countries have used the military to control civil disorder, let alone authoritarian regimes: India in Kashmir, for example. President Trump made it clear he was willing to do the same against Black Lives Matter protesters. Under the Basic Law there are powers to use the 6,000 troops deployed in the territory in an emergency. Yet the regime stayed its hand (and got no credit for exercising restraint), choosing instead to deploy the draconian National Security Law.

Western critics have been horrified that the law has extra-territorial reach, but in this respect China is simply copying American practice. British individuals have faced extradition to the US to face criminal courts though they never have set foot there. Now China will apply the same principle.

What is even less surprising is that China has not evolved into a competitive multi-party democracy like Korea and Taiwan (but not Singapore, Vietnam or, now, Thailand). The architect of modern China, Deng Xiaoping, made it absolutely clear – brutally so, at Tiananmen Square – that political liberalisation does not inevitably follow economic liberalisation and the embrace of capitalism. He attacked Gorbachev as a “fool” for linking the two issues.

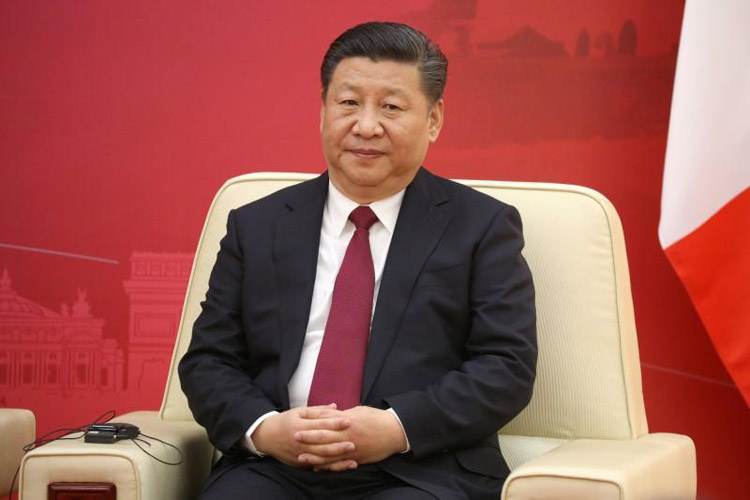

Deng’s clear view, which Xi has re-articulated, is that the Communist Party must remain in control. These days the party has little to do with communism and is more a political vehicle for a competent, meritocratic, ruling elite. Western leaders who claim to have been “let down” when engaging with China, now that democracy has failed to appear, are either dishonest or dim.

However, the present regime in Beijing has things to learn from Deng too. He always encouraged modesty and lack of arrogance. By contrast, the Chinese government is currently making a lot of unnecessary enemies by overreacting to criticism and using the belligerent language of the “wolf warriors”. Prickly, proud nationalism is coming across as aggressive, and is detrimental to China’s interests.

Some of Deng’s earthy humour and common sense would also have been a better reaction to the British government’s offer to take 3 million Hong Kong residents who hold British overseas passports. China could have called the UK’s bluff: “be my guest; take them.” Instead, Chinese threats and bluster have had the effect of consolidating an improbable coalition of parties from the left and right, determined to confront China over Hong Kong. They are backed by that improbable champion of human rights, Donald Trump.

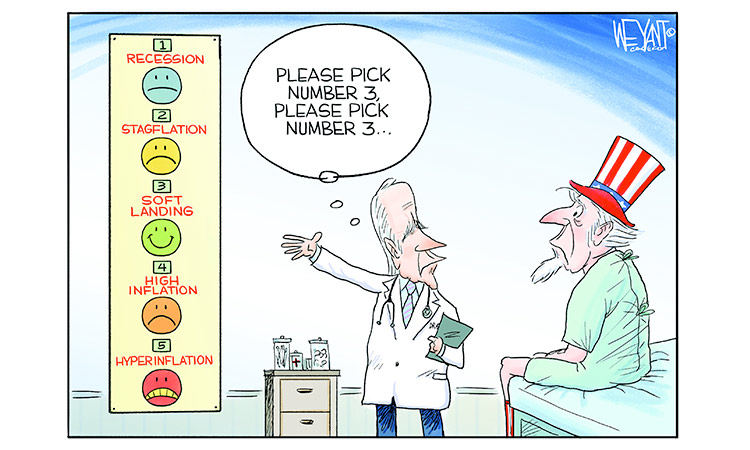

Today Trump will claim a useful scalp when the British government capitulates to US demands that Britain cuts Huawei out of its future 5G network – despite clear evidence that the company is valuable to the UK and can be managed. As Sir John Sawers, the former head of MI6, has already pointed out, threats of US sanctions have made the British position untenable.

Long gone are the days when a British government could defy the US – as it did initially over Huawei, and earlier when the coalition government backed the Chinese initiative to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. Indeed, the UK-US trade agreement which the government craves will go further with a “poison pill” clause forbidding Britain from negotiating a trade deal with China.

Brexit Britain’s role is clear: to be chief cheerleader in a US-led “coalition of the willing” against China.