America should shed its hatred for Syria

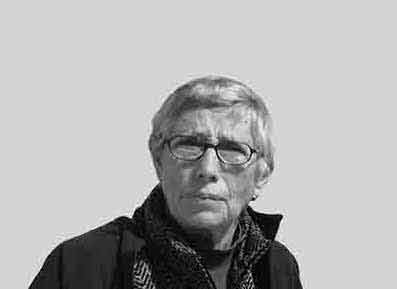

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

In May of this year, Saudi Arabia restored relations with Syria and its suspension from the Arab League ended. Abu Dhabi and Riyadh have called on Europe to follow suit. Western sanctions are preventing expatriate Syrian, Arab and foreign investments in reconstruction, economic recovery and lifting 90 per cent of Syrians out of poverty. Syria’s return to normality is essential for the wellbeing of the citizens of this region and its overall stability.

Following the US example, France and Germany have refused to normalise ties with Syria and, instead, have ratcheted up sanctions. This has deepened the economic and social crisis in Syria while Lebanon and Jordan have been pressing hard for the repatriation of more than 2.8 million Syrian refugees. Neither Syria nor these two countries can sustain the costs of hosting so many Syrians while Syria and their countries are suffering economic meltdown.

The Syria-UN “understanding” allows for UN deliveries of humanitarian aid through Bab al-Hawa and two other crossings, Bab al-Salamah and al-Rai to western Idlib and adjacent tracts of territory in Aleppo and Latakia provinces. While Bab al-Hawa has remained open for commercial and civilian traffic, UN and allied agencies supplies were halted with the expiry of the Security Council resolution mandating deliveries for six months, the practice of several years.

When this mandate came up for renewal by the Council, the US, France and Britain called for year-long authorisation. This was rejected by Syria’s ally Russia which insisted on six months and dismissed a nine-month compromise. Russia used its veto as a permanent Council member and turned over the matter to Syria. Damascus insists that the Council’s intervention was no longer valid because fighting had ceased and Syrian sovereignty had to be restored along the conflicted border with Turkey. Ankara occupies enclaves of Syrian territory and provides protection for al-Qaeda offshoot Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) which rules western Idlib. Although HTS, a takfiri group, is branded a “terrorist” organisation by the UN, US, and Europe, they are quite happy to deal with HTS.

Damascus initially demanded that the UN should halt contacts with “terrorists” and insisted that the International Committee of the Red Cross and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent should supervise deliveries of aid, although neither has a major presence in HTS-held areas. These conditions have been dropped by the government which made major gains by reaching what the UN calls an “understanding.”

The government has reasserted control over Bab al-Hawa, through which 85 per cent of aid crosses into northwestern Syria and the Security Council no longer has control over UN traffic through Bab al-Hawa. Having reopened the other two crossings to accommodate increased aid after the devastating February earthquakes, the government has also agreed to allow them to carry on until November.

The US has not been in favour of or impressed by Arab normalisation with Syria which was given impetus by the reconciliation between Saudi Arabia and Iran, Syria’s ally, after seven years of estrangement. Sunni Saudi Arabia severed relations with Shia Iran in 2016 after its embassy in Tehran and consulate in the north-western city of Mashhad were attacked by Iranians during protests over the Saudi execution of dissident Shia cleric Nimr al-Nimr.

Washington sees Syria as a dependent of Russia and Iran, two longstanding US adversaries. Their military intervention in Syria’s civil and proxy conflicts has enabled the government to recoup territory from opponents so that Damascus now rules 70 per cent of Syria. Without Russian and Iranian aid, Syria might have been fractured into warring fiefdoms held by warlords.

Russia is regarded as heir of the Soviet Union (USSR) which backed Syria against Israel and the West until the USSR collapsed in 1989. Russia has also alienated the West by waging war on Ukraine due to its determination to join NATO, the Western alliance Moscow sees as a threat to “Mother Russia.”

Since the revolution of 1979, Iran has deprived the US of one of its lucrative economic assets and military bases in this region. After Iranian clerics ousted the US-allied Shah, Washington has regarded Tehran as regional enemy-number-one although Iran has done nothing to harm the US and little to challenge US interests. US antipathy is visceral and has endured through the reformist presidencies of Hashemi Rafsanjani, Mohammed Khatami, and Hassan Rouhani. Rafsanjani made efforts to overcome US antagonism, Khatami launched a global campaign to win over Western powers, and Rouhani negotiated the 2015 agreement to limit Iran’s nuclear programme in exchange for lifting sanctions. This could have effected a major change in US policy toward Iran and led to rapprochement between Tehran and the West.

In 2018, the deal was abrogated by Donald Trump who took his cue from Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu who has called for war on Iran throughout his three terms in office. Trump’s withdrawal of the US from the deal has empowered Iran’s anti-US hardline clerics and, in the absence of limits set by the deal, encouraged Iran to advance its nuclear programme without enriching uranium to the bombmaking level of 90 per cent.

Washington’s policy toward Damascus has been driven by US visceral antagonism and Israel’s hostility towards Iran. Instead of trying to reduce Syria’s reliance on Russia and Iran, the US has enhanced and deepened its dependency by imposing destructive sanctions on Syria which punish foreign governments, businesses and individuals seeking to trade with Syria and rebuild the country. Once Syria has reconstructed villages, towns and cities and recovered economic viability, the country would regain independence of decision making and action. Washington’s politicians and officials remain stuck in a Cold War mentality although Russia is not the USSR and pointless longing for the dethroned Shah’s subservient regime in Iran.