Palestinian factions joining forces not a reconciliation

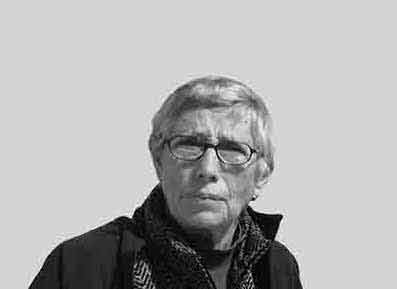

Michael Jansen

The author, a well-respected observer of Middle East affairs, has three books on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Palestinians protest against Israel’s plan to annex parts of the West Bank, in the West Bank village of Kufr Qaddum near Nablus. File / Associated Press

If NOT for reconciliation, why is this agreement a landmark?

Firstly, the rivals have decided to come together for a specific purpose: resistance to annexation if Israel goes ahead with the plan put forward by Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu. Fatah and Hamas are not trying to establish common governance this time round. This has been attempted repeatedly with Saudi Arabia and Egypt acting as facilitators and has repeatedly failed, largely because President Mahmoud Abbas is not prepared to share power with Hamas.

With the threat of annexation hanging over his head, Abbas began by halting Palestinian cooperation and coordination with Israel. He has now agreed to a unity-in-resistance effort which could involve violence. This amounts to a dramatic change of policy for Abbas who has consistently rejected violence since taking office in 2005. His predecessor, Yasser Arafat, never gave up on the armed struggle and used the threat it posed as leverage in negotiations with Israel and with its friends with the aim of getting them to restrain Israel.

Secondly, the resistance option has increasing legitimacy because Israeli annexation of Israel’s illegal colonies and the Jordan Valley, 30 per cent of the occupied West Bank, is opposed by the UN, European Union as a bloc, Russia, and Israel’s Western allies with the exception of the Trump administration. It has given a green light to the move, but appears to have asked Netanyahu to delay and carefully consider consequences.

Although there has been no response from Western governments, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has not only welcomed the unity-in-resistance agreement but also urged Arab governments to follow Moscow’s example. He called for the resumption of Palestinian-Israeli talks under the aegis of the Quartet and with Arab participation. Netanyahu’s hesitant coalition partner, Blue and White’s Benny Gantz, has conditioned annexation on consultations with the Palestinians while Israelis on the left and in the centre of the political spectrum oppose annexation. The West Bank colonists movement is also in opposition since under the Trump plan — which Netanyahu is using as his pretext — a Palestinian state should emerge in the 70 per cent remaining. The colonists flatly reject a Palestinian state.

Thirdly, the agreement has been announced by two prominent West Bank figures. While the Hamas leadership in Gaza has approved, Arouri has acted in his capacity as the movement’s chief in the West Bank and Rajoub as head of the West Bank-based central committee of Fatah. Both men have had long careers as militants.

Rajoub joined Fatah as a youth and spent many years in Israeli prisons for resistance activities. In 1988 he was deported to Lebanon from where he went to Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) headquarters in Tunis. He worked as an adviser to Kahlil al-Wazir, head of PLO military operations. After Wazir’s assassination Rajoub joined the staff of PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat. Following the 1993 signing of the Oslo Accord and Arafat’s return to Palestine, Rajoub served as head of Palestinian preventive security from 1994-2002 during which time he cracked down on Hamas which opposed the Oslo deal.

From conservative al-Khalil (Hebron), Arouri was recruited by Hamas while at university. He set up a Hamas military organisation in the West Bank, becoming a founding commander of the movement’s Izzedin al-Qassam brigades. He spent 15 years in Israeli prisons and has a $5 million US bounty on his head for mounting recent attacks on Israelis in the West Bank. He appears to shift his base from Beirut, to Istanbul and Doha.

Fourthly, during their virtual press conference, Rajoub in Ramallah and Arouri in Beirut vowed to “speak in a single voice.” Rajoub said they would “mount “popular resistance in which everyone participates” and “put in place all necessary measures to ensure national unity” in the campaign against annexation.

Rajoub announced, “We will not raise a white flag, we will not give up. All the options are open if the Israelis start the annexation and slam the door on the two-state solution.” He said the form of resistance adopted by the Palestinians would depend on Israel and suggested there could be a third Intifada to end the occupation and “remove annexation from the table.”

Arouri stated, “All the controversial issues on which we differ, we will set those aside… We and Fatah and all the Palestinian factions are facing an existential threat, and we must work together.” Hamas, he said, will use “all forms of struggle and resistance against the annexation project.” Every Palestinian “is a soldier in this work, each in his own way, whether a journalist, a politician, a diplomat, or an infantryman.”

He asserted, “Annexing any percentage of the West Bank now means that more will follow... If the occupation ends up controlling the Jordan Valley, Jerusalem and other areas then (Israel) will have an appetite for more.”

Finally, since Palestinian security cooperation with Israel has been suspended due to Netanyahu’s annexation plan, the Fatah-Hamas agreement could mean that mass demonstrations could erupt without hindrance and militants from all factions could be free to mount attacks on Israel and Israelis.

This being the case, it is significant that most of the Western press did not make much of this development although it was widely reported in the Arab world and in Israel.